Can we trust what we see?

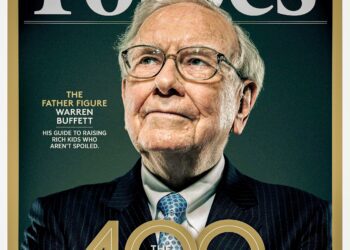

Fred Ritchin has been thinking about the future of the photograph for nearly half a century. He started to notice changes to the medium in 1982, working as picture editor at the New York Times Magazine; in 1984 he wrote an article for the magazine, “Photography’s New Bag of Tricks,” about the consequences of digital editing technology in contemporary photojournalism. In the decades since, he’s witnessed the shift from the early days of digital photo editing to AI imagery, in which amateur and professional users alike can use digital services to instantly generate realistic visuals.

As AI images become increasingly common, Ritchin feels people need to find new ways to confirm that they can believe what they see. Of course, AI imagery hasn’t emerged out of thin air. Ritchin traces a through line from contemporary conversations on best practices for AI back to those in pre-Photoshop times about whether journalists should disclose altering photographs. In the early days of digital editing, National Geographic was criticized for digitally moving the Pyramids at Giza closer together for its February 1982 cover image. Today National Geographic photographers are required to shoot in RAW format—a setting that produces unprocessed, uncompressed images—and the magazine has a strict policy against photo manipulation.

Ritchin’s view is that editors, publishers, and photojournalists should respond to the challenges of AI by setting clear standards; media and camera companies have begun developing options to automatically embed metadata and cryptographic watermarks in photographs to show when an image was taken and whether it’s been tampered with via digital editing or AI alterations. While Ritchin doesn’t call for rejecting AI entirely, he hopes to reinvent the unique power that photography once held in our personal and political lives.

Do we have to accept that machines are fallible?

In a particularly funny moment, a recent study showed that one of the most popular AI chatbots many people rely on has been sharing inaccurate coding and computer programming advice. That’s a big issue facing AI right now—these evolving algorithms can hallucinate, a term for what happens when a learning model produces a statement that sounds plausible but has been completely made up.

When humans make mistakes, Ghani says, it’s easy for us to empathize, since we recognize that people aren’t perfect beings. But we expect our machines to be correct. We would never doubt a calculator, for instance. That makes it very hard for us to forgive AI when it gets things wrong. But empathy can be a powerful debugging tool: These are human-made systems, after all. If we take the time to examine not only AI’s processes but also the flawed human processes underlying the datasets it was trained on, we can make the AI better and, hopefully, reflect on our social and cultural biases and work to undo them.

How do we confront the environmental impact?

AI has a water problem—really, an energy problem. A significant amount of heat is generated by the energy required to power the AI tools that people are increasingly using in their daily personal and professional lives. This heat is released into data centers, which provide those AI systems the computational support and storage space they need to function. And, as Shaolei Ren, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at UC River-side, is quick to note, cooling down the data centers requires an enormous amount of water, similar to the amount used by tens of thousands of city dwellers

Even before the current AI boom, data centers’ water and energy demands had steadily increased. In 2022, according to Google, its data centers used over five billion gallons of water, 20 percent more than in 2021; Microsoft used 34 percent more water companywide in 2022 than in 2021.

Read the full article here

By Neel Dhanesha and Charley Locke / National Geographic