Experts are struggling to figure out where the world economy is headed.

Leaders and expert can’t really decide on wether the world economy will bounce back or it won’t.

As world leaders arrive at Davos, Switzerland for the World Economic Forum’s 50th annual summit, major international organizations cannot seem to concur on the future of GDP global growth.

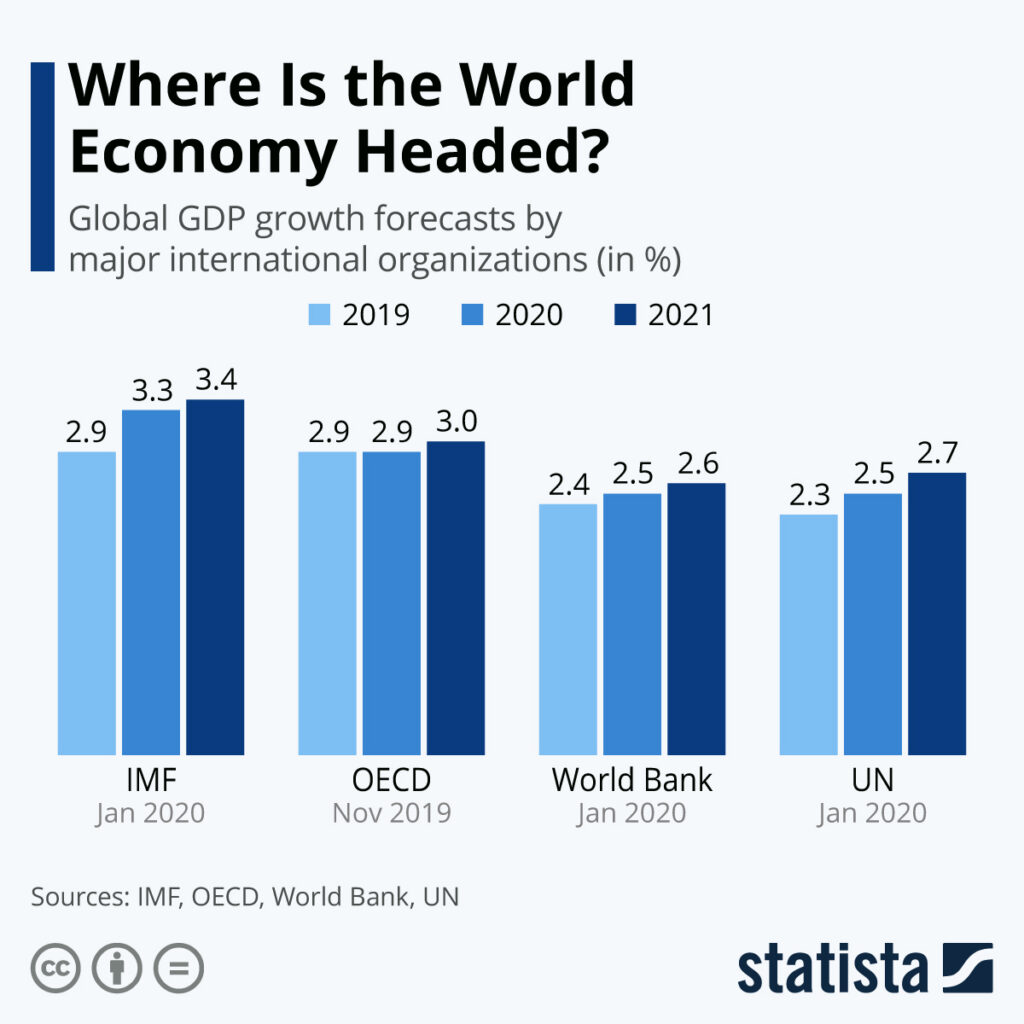

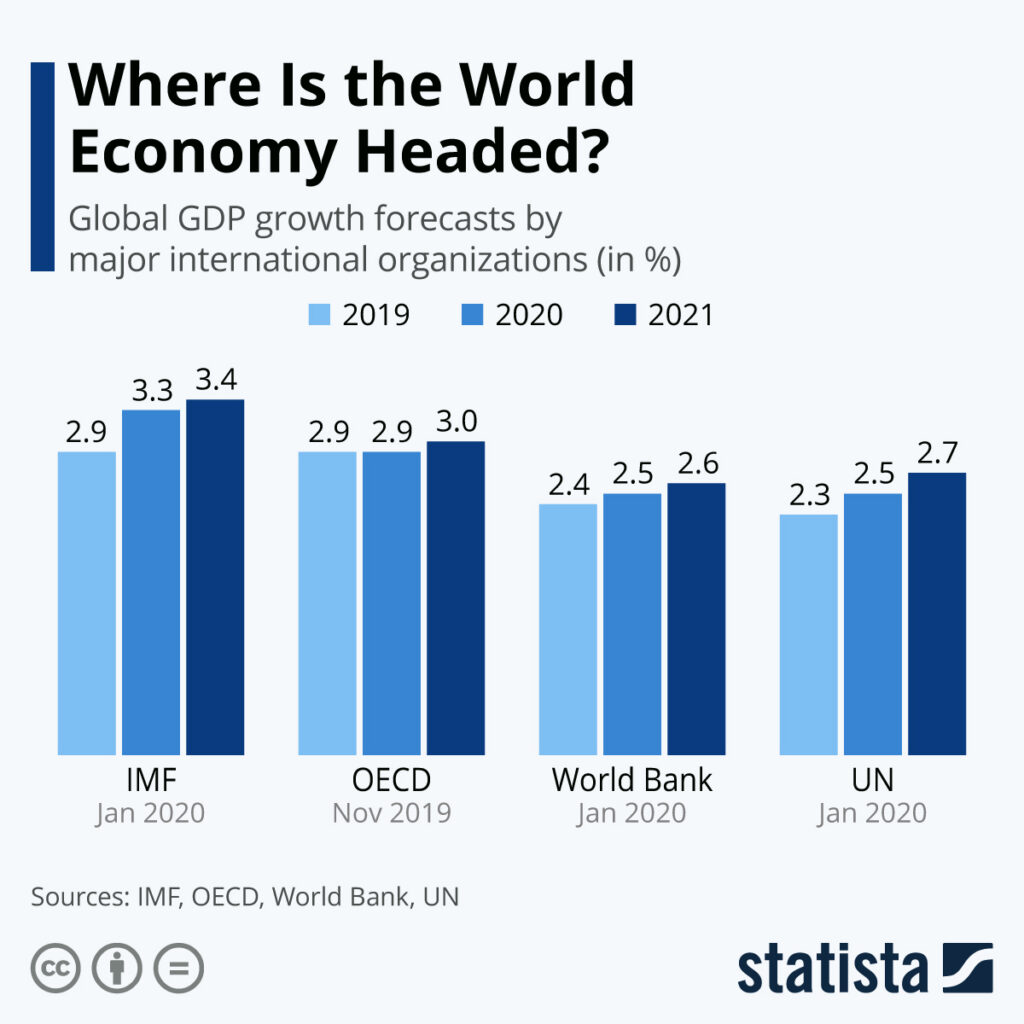

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) remains relatively optimistic compared to other forecasting options, putting GDP growth at 3.4%, arguing that although few signs of turning points are yet visible in global macroeconomic data, market sentiment has been boosted by tentative signs that manufacturing activity and global trade are bottoming out, a broad-based shift toward accommodative monetary policy is happening, and intermittent favorable news on US-China trade negotiations as well as diminished fears of a no-deal Brexit have led some retreat from the risk-off environment that had set in, however, no other report from another major international organizations expects the world economy to bounce back as quickly in 2020 and 2021 as the IMF does.

The OECD report forecasts a 3% growth range – the weakest reported annual growth rate since the financial crisis of 2008, reporting escalating trade conflicts, politic uncertainty, persistent weakness in manufacturing sectors, and downside risks continuing to mount as the main challenges for confidence, growth and job creation across the world economy.

“The global economy is facing increasingly serious headwinds and slow growth is becoming worryingly entrenched” (…) “The uncertainty provoked by the continuing trade tensions has been long-lasting, reducing activity worldwide and jeopardising our economic future. Governments need to seize the opportunity afforded by today’s low interest rates to renew investment in infrastructure and promote the economy of the future,” said OECD Chief Economist Laurence Boone.

The World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020 from the United Nations (UN), on the other hand, warns that economic risks remain strongly tilted to the downside, stating that growth of 2.7% in 2020 is possible, but a flareup of trade tensions, deepening political polarization, financial turmoil and increasing scepticism could derail a recovery.

“Policymakers should move beyond a narrow focus on merely promoting GDP growth, and instead aim to enhance well-being in all parts of society. This requires prioritizing investment in sustainable development projects to promote education, renewable energy, and resilient infrastructure,” emphasized Elliott Harris, UN Chief Economist and Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development.

Finally, the World Bank, on its own document, projects a steep productivity growth slowdown in emerging and developing economies, projecting global growth at at 2.6% for 2020, just above the post-crisis low registered in 2019. It continues reporting a high possibility of a re-escalation of global trade tensions, policy uncertainty, financial disruptions inside corporations, and sharp downturns for some major economies.

“With growth in emerging and developing economies likely to remain slow, policymakers should seize the opportunity to undertake structural reforms that boost broad-based growth, which is essential to poverty reduction” (…) “Steps to improve the business climate, the rule of law, debt management, and productivity can help achieve sustained growth,” said World Bank Group Vice President for Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu.

As the following Statista chart shows, estimates for this year’s global economic growth range from 2.5% (World Bank and UN) to 3.3% (IMF).

An expanding US economy – a sliding China side

Based on estimates about regional sustainable growth in the labor force and productivity, IHS Markit sees potential growth in the US economy of around 2%, stating that the run-up to the 2020 presidential election could provide some policy surprises, both positive and negative.

On the other side of the trade war, an aging population, and a decade-long deceleration in productivity growth could make China’s growth rate slide even further. This large drop, according to the global information provider, suggests China’s model of state-controlled development is running out of steam and the country is at risk of falling into the middle-income trap of diminished growth potential.

Click here to read more about its economic projections for 2020.