New Columbia Business School research challenges assumptions about AI art’s impact: Rather than diminishing human creativity, the presence of AI-generated art can actually enhance the perceived value of human-made work.

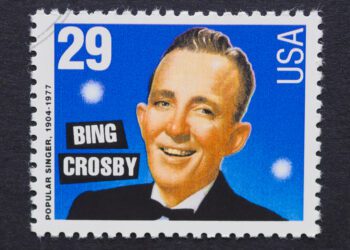

In November 2024, a portrait of British mathematician Alan Turing made history by selling at auction for $1.08 million. That figure may sound unexceptional in today’s market — until you realize that the artist, Ai-Da, is a robot and the art is AI-generated.

Generative AI technology is quickly encroaching on the art world, challenging the age-old philosophical belief that artistic creation is a quintessentially human experience. This development is provoking both economic and existential anxieties among anyone who makes a living from creative work. If AI can make art, does human artwork still have value? Will human artists who earn income through their work lose their livelihoods?

To address these questions, doctoral candidate C. Blaine Horton Jr. enlisted the help of Sheena S. Iyengar, the S. T. Lee Professor of Business in the Marketing Department at Columbia Business School. Although she is blind, Iyengar often visits museums to immerse herself in viewers’ responses. Fascinated by the subjective experience of visual art, she provides a unique perspective for studying the perceived value of art.

Along with Michael W. White, also a doctoral candidate, Horton and Iyengar designed a series of experiments to measure how the source of an artwork — AI or human — influences a viewer’s perception of the creativity and skill behind the work, as well as its monetary value.

Key Takeaways:

- The rise of AI-generated art is provoking anxiety about the future of human-made art.

- In a recent study, participants valued art labeled as AI generated 62 percent lower than art labeled as human made.

- Although human-made art had a higher perceived value when displayed next to AI art, no such increase occurred when shown next to other human art.

- Even in a market affected by AI art, human artists may be able to preserve their pricing by drawing clear distinctions between their work and AI-generated pieces.

Designing the Study

Before conducting the experiments, the researchers selected 28 images, half of them lesser known works by artists such as Paul Gauguin and Andy Warhol and the other half AI generated to resemble those styles. A pretest confirmed that participants generally could not distinguish between human-made art and AI-generated works, even when they felt strongly that they could. The pretest also ensured that all images were stylistically comparable, so that any differences in perception would be due to labeling rather than variations in artistic quality.

In the first experiment, the researchers presented participants with human- and AI-generated art with no origin labels. Images were left unlabeled to avoid priming participants toward AI-related biases, thus establishing a control. In subsequent experiments, the researchers varied the conditions, randomly assigning labels of AI made, human made, or collaboratively made. They also changed the presentation order of the AI- and human-labeled art to minimize potential bias in participants’ judgments.

Humans Prefer Human-Made Art — or at Least, They Think They Do

The study found that participants were willing to concede that AI-generated art shows the same level of skill and nuance as human-made art. But they were markedly biased against AI art when it came to measures of creativity, the amount of labor involved, and monetary value. In fact, in one of the exercises, participants valued AI-labeled art 62 percent less than art identified as human made.

The participants’ bias didn’t surprise Iyengar. “Although AI may replicate a style, it can never capture the deep narrative forged by human effort and intuition,” she says. “The labor, creativity, and passion that characterize human artistry endow each work with an intrinsic value that a machine cannot achieve.”

There’s an important caveat to these findings, however: Participants deemed art labeled as human made as more creative and valuable only when presented alongside art labeled as AI generated. When evaluating a piece without any references to AI, they did not accord the same piece of unlabeled work a higher value.

The same bias against AI art appeared in the experiment involving art identified as “collaborative.” When presented with artwork labeled as produced jointly by humans and AI, participants deemed it less creative, labor intensive, and valuable than human-made art — but more so than art made solely by AI.

An Unexpected Opportunity for Artists

Although the rise of AI art might lower the market value of artwork overall, Horton’s research offers hope: Artists who emphasize that their work is human made, with no AI involvement, could actually command higher prices.

“It would behoove artists to remind people that a lot of the art they buy on Etsy is algorithmically produced, but the art in front of them at an art fair is made by hand,” Horton says. “That can drive up the perception that what they’re doing is valuable and creative.”

Of course, there’s still the issue of how prospective buyers can be certain of an artwork’s origin. “It’s a good question, but I think we’ll start to see more interesting and innovative practices,” says Horton. “I’m waiting for the day when I’m scrolling through my algorithm and see a ‘Verified Human Content’ label. And there are other ways in which you can start to make the human action of it more visible.” He cites the example of a museum employing an artist to paint something in person in the lobby and then offering that work for sale.

Horton speculates that art created by AI may become its own category. We’ve seen this in the past with artistic fields like photography, which, initially feared as the death of portraiture, evolved into a separate genre, he notes. There’s even a new term that’s been floated for this emerging class of AI art: synthography.

Beyond creating new artistic genres, AI’s influence might have an even more surprising effect on human creativity: making artists better at their craft. Horton points to a precedent for machine-prompted human evolution. With the advent of computer chess programs, the perception of a human grandmaster’s skill declined because the computer made the mastery of chess seem easier than it is. But despite the initial threat posed by computers, human grandmasters eventually became even better at the game because they could train against machines.

“It remains to be seen whether the same thing will happen in the art world,” says Horton. “If so, human value and the idea of human expertise should decrease or be variable for a period of time, until the machine surpasses us and a new bar is set for what it means to be a good artist.”