US newspapers have been hit hard as more Americans consume news digitally, and Pew Research explored the patterns and longitudinal data.

Are newspapers losing their battle against the internet and digital news? That’s the raging debate.

It’s no doubt that the Internet came to kill the only economic model newspapers had ever known, causing them troubles to adapt and prosper. Particularly in economics, total estimated advertising revenue for the newspaper industry during 2018 was $14.3 billion, dropping 13% in comparison from 2017, all while digital advertising accounted for 35% of newspaper advertising revenue, and is expected to rise to 19.1% this year to reach $129.34 billion in 2019, according to eMarketer estimates.

Google, Amazon, and Facebook —all tech-driven, nontraditional publishers— seem to have cracked the code for digital advertising while newspapers and magazines struggle to increase digital ad earnings, proving the power of digital over traditional media.

Not all legacy print media companies are struggling, some are even diversifying their business models, but their successes are largely due to surges in subscription revenues rather than with other traditional ways.

Investment also at risk

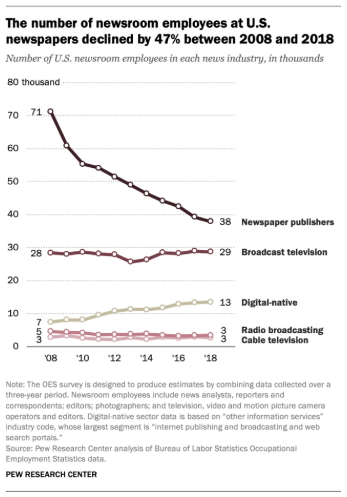

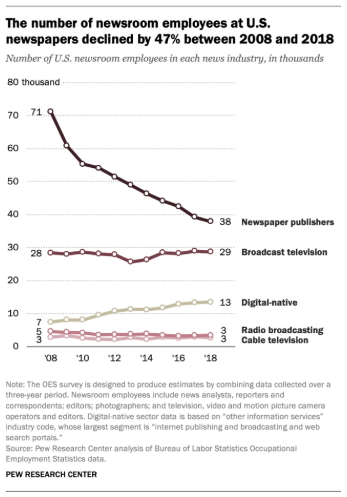

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment Statistics revealed recently that 37,900 people worked as reporters, editors, photographers, or film and video editors in the newspaper industry during 2018, a 14% loss from 2015 and 47% from 2004.

Elizabeth Grieco, from Pew Research Center, reported that newsroom employment across the United States continues to decline, driven primarily by job losses at newspapers and even despite that digital-native news outlets have experienced some recent growth in employment. From 2008 to 2018, newsroom employment in the U.S. dropped by 25%. In 2008, about 114,000 newsroom employees – reporters, editors, photographers and videographers – worked in five industries that produce news: newspaper, radio, broadcast television, cable and “other information services” (the best match for digital-native news publishers). By 2018, that number had declined to about 86,000, a loss of about 28,000 jobs.

This decline in overall newsroom employment has been driven primarily by one sector: newspapers.

Social media hasn’t helped either. In December 2018, for the first time since Pew Research Center began asking questions about media usage and customs, social media outpaced newspapers as the more preferred news source. Over 1 in 5 U.S. adults say they often get news via social media, slightly higher than the share who often do so from print newspapers (16%).

Overall, television is still the most popular platform for news consumption – even though its use has declined since 2016.

Another big foe: Misconception

While print media’s struggle to turn profits is apparent to those who closely follow the ad industry, it isn’t as clear to the general public.

In the fall of 2018, Pew Research Center conducted a poll of 2018 of 34,897 U.S. adults, finding that 71% of respondents believe their local news outlets were doing well financially. When it comes to their own financial support of the industry, just 14% of American adults say they have paid for local news in the past year, either through subscription, donation or membership. When those who don’t pay were asked why, the widespread availability of free content tops the list (49%).

Overall, Americans evaluate their local media fairly positively, as 30% of Americans are very confident that their main news source can get them the information they need, with another 52% saying they are somewhat confident.

“We are dealing with at least two generations of people now who have grown up without the newspaper-reading habit, and with the idea that news should be free”, says Ben Bradlee, Jr., former editor at the Boston Globe. “Sadly, most people these days seem not to care about reading a paper thoroughly, or about being well-informed. Scandalously, 42% of people eligible to vote in the recent presidential election did not do so.”

Content, quality, and freedom of speech are at stake. As newsrooms have been decimated by job cuts, too many editors have concluded that investigative reporting, debates, and other journalistic specialities are a luxury they can do without. They’re wrong. It’s essential—especially today.