Closing the gender employment gap could lift Japan’s GDP by 10%.

By Kathy Matsui, Hiromi Suzuki and Kazunori Tatebe of Goldman Sachs

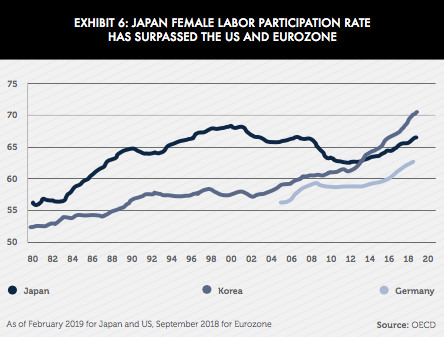

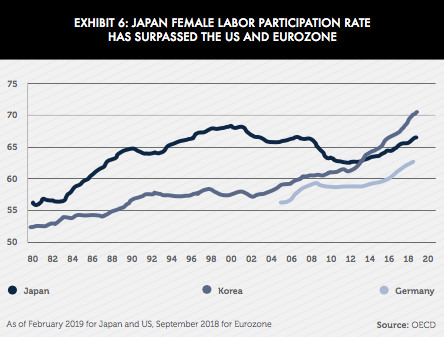

Since our initial Womenomics report in 1999, Japan now enjoys record female labor participation (71%) that surpasses the US and Europe, generous parental leave benefits, improved gender transparency, and labor reforms. Areas for improvement include: a dearth of female leaders, gender pay gaps, inflexible labor contracts, tax disincentives, insufficient caregiving capacity, and unconscious biases.

However, the reward for persistence is potentially sizeable.

Specifically, suggested government policies include: more flexible labor contracts, gender pay gap disclosures, tax reforms, parliamentary gender quotas, promotion of female entrepreneurship, and looser immigration rules. For corporations: proactive career management, more flexible work environments, performance-based evaluations, gender target-setting, and male diversity champions. Elsewhere, society should dispel Womenomics myths, avoid gender role stereotypes in the media, and promote more women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Fortunately, tailwinds such as Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) investing and shifting millennial male attitudes should further advance Japan’s diversity agenda.

Two decades have passed since we published our first report on Womenomics: Buy the Female Economy. In 1999, the term “diversity” was neither part of the Japanese vernacular, nor a focus for the government, company managers, or society. Fast forward to 2019, and as a result of widespread labor shortages and a growing economy, there is a growing realization that gender diversity in the workplace is no longer an option, but an economic and business imperative.

To mark the 20th anniversary since our initial Womenomics research, we take stock of progress thus far, identify areas for improvement, and propose concrete recommendations for the future:

1. What’s the economic and business rationale behind womenomics?

Updating our 2014 simulation whereby Japanese female labor participation rises to that of males, the potential boost to Japan’s GDP could be 10%. However, under a “blue-sky” scenario, if we also assume the ratio of female vs. male working hours rises to the OECD average, the GDP boost could expand further to 15%. For businesses, Japanese listed firms with higher female manager ratios tend to deliver higher ROEs and sales growth.

2. What progress has been seen since 1999?

Over the past two decades, Japan has: a) seen its female labor participation ratio surge to a record 71%— surpassing the US and Europe, b) introduced one of the most generous parental leave benefits in the world, c) improved its gender transparency, and d) approved workstyle reforms that mandate overtime limits and equal pay for equal work.

3. What areas still need improvement?

Areas that still need work include: a) a dearth of female leaders in both the private/public sectors, b) persistent gender pay gaps, c) inflexible labor contracts, d) tax disincentives, e) insufficient caregiving capacity, and f) unconscious biases.

4. What should the government, corporations, and society do now?

Policy recommendations include: more flexible labor contracts, gender pay gap disclosures, tax reforms, parliamentary gender quotas, promotion of female entrepreneurship, and looser immigration rules. For corporations, leaders should proactively manage women’s careers, promote more flexible work environments, shift to performance-based evaluations, set gender diversity targets, and engage male diversity champions. Society should dispel Womenomics myths, shift gender role stereotypes in the media, and encourage more girls and women to pursue STEM education and careers.

The good news is that there are two important tail-winds today that were absent in 1999 that should help advance the Womenomics agenda over the next 20 years: namely, the major expansion of ESG investing and shifting attitudes of the younger generation.

Why womenomics? The economic and business case

When we first broached the topic of Womenomics and the need for greater gender diversity in 1999, our argument was not social or cultural, but rather a simple economic one. After all, the three key determinants of economic growth for any country are: labor, capital, and productivity.

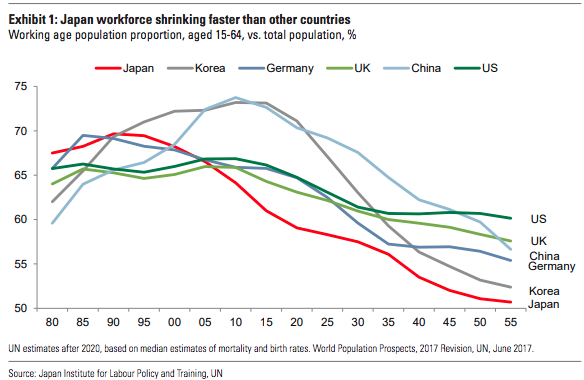

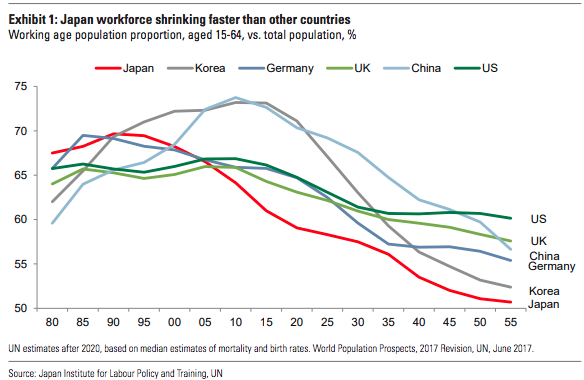

Since Japan’s population is shrinking, capital is finite, and productivity gains will take time. Unless radical steps are taken quickly, we argued that the nation not only faced the risk of a further decline in its productivity and potential growth rate, but eventually, lower standards of living as well.

Demographic tsunami

Since our last Womenomics report in 2014, Japan’s demographic situation has deteriorated even further. Indeed, in 2018, the IMF warned that in the absence of meaningful structural reforms, demographic headwinds could cause the level of Japan’s real GDP to decline by over 25% in 40 years relative to a baseline projection where productivity and population grow at their recent pace.

How Japan chooses to manage its demographic headwinds over the next several years will serve as an important template (or not) for how other countries should cope with their own aging societies. After peaking in 2008 at 128 million, Japan’s overall population had already shrunk by 1.5% to 126 million in 2018, and based on government projections, is forecast to drop by 30% to just 88 million by 2065. More importantly, by 2055, Japan’s workforce population is expected to shrink dramatically by 40%, from 75 million in 2018 to 45 million.

The government aims to boost the fertility rate to 1.8 by 2025, but as of 2018, it stood at just 1.4. Japan remains one of the few major countries where the number of registered pets (18.7 million dogs and cats alone as of 2015) outnumbered children under the age of 15 (16.6 million).

Besides shrinkage, Japan’s population is also aging more rapidly than most other nations, with 28% of Japanese already in the elder-age cohort (65 years and older), and by 2055, this ratio is projected to rise to 37%. Furthermore, Japan’s old-age dependency ratio (the number of elder persons supported by one active worker) will rise to around 75% by 2050—the highest of any nation globally—meaning that eventually, each Japanese worker will need to support 1.3 elderly persons. This will pose even more serious challenges to the nation’s fiscal debt sustainability.

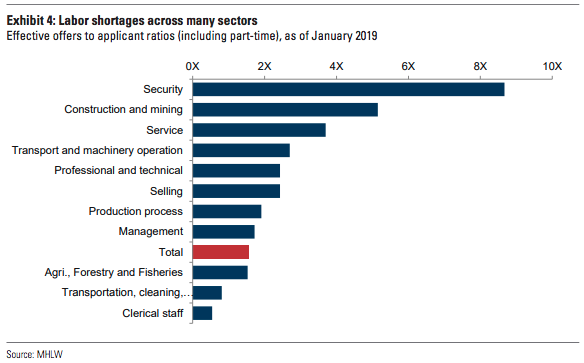

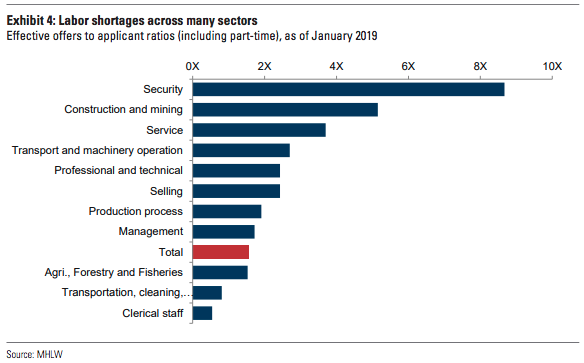

Consequently, Japan’s labor market has become extremely tight, resulting in the unemployment rate sinking to a quarter-century low of 2.3% in February 2019 and the job offers-to-applicants ratio reaching a record 1.6X—meaning there are 60% more jobs available than Japanese seeking work.

Unsurprisingly, labor-intensive industries such as security services, construction, and transportation are facing the most acute shortages. Although foreigners have provided some relief, ongoing job shortages recently prompted the government to approve legislation which allows longer-duration work visas (max. 5 years) for up to 345,000 foreign nationals in five specified industries such as caregiving, construction, hospitality, shipbuilding, and agriculture. This new visa program started April 1, 2019 and will last for the next five years. While this should ease some of the shortages, we doubt it can fill the entire supply gap.

Therefore, continuing to expand female employment must remain a top priority for the Japanese government and society.

Record female labor participation

When we published our first Womenomics report in 1999, Japan’s female labor participation rate stood at just 56%—one of the lowest in the developed world.

Since then, however, the percentage has risen sharply to nearly 71% (as of Feb. 2019), overtaking the US (66%) and the Eurozone (62%) (Exhibit 6). Growth in the number of working women has been particularly pronounced during the past six years of Abenomics, where the number of employed females surged by more than 3 million from 26.4 million in 2012 to 29.7 million in 2018.